The Cloak of Concentration: the corporatisation of media

Declining Print Circulation and Rising Media Concentration

The media sector and publishing industry have undergone significant transformation over an extended period. Pressure on media companies to transition the traditionally lucrative newspaper business toward a digital future—one in which both media consumption and format have changed dramatically—continues to mount. An ever more apparent outcome of this dynamic is consolidation: media companies are consolidating market shares and centralizing operations to distribute declining profit margins across fewer hands.

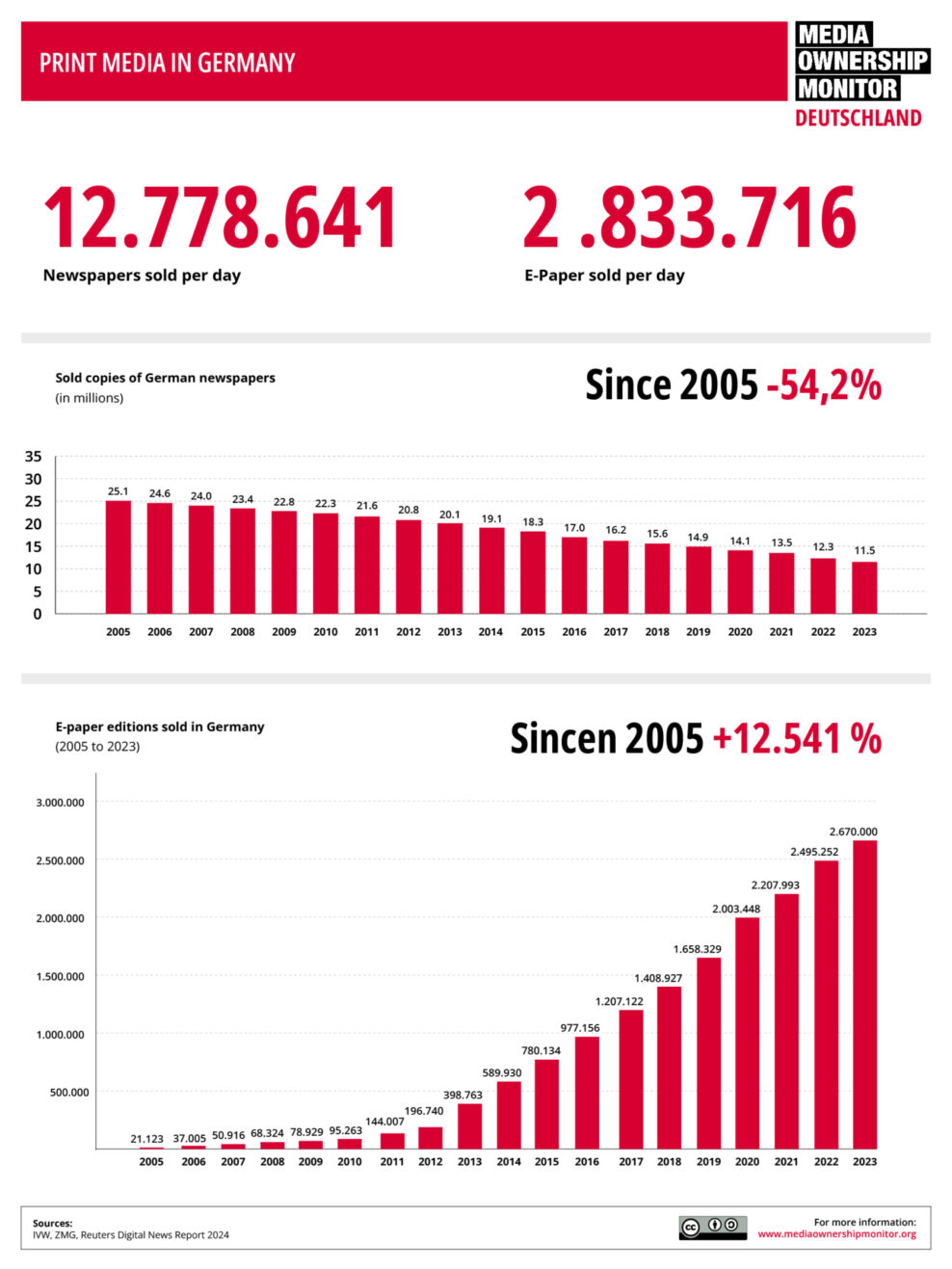

Since 2005, circulation of printed daily newspapers in Germany has declined by more than 54 percent. Despite rising digital subscription revenues, the total newspaper industry revenue across Germany has declined over the past three decades, reflecting the decrease in sales and the overall shrinking market. According to industry analysis, total sector revenue in Germany stood at approximately €6.3 billion in 2024, with projections indicating a further decline of 4.5 percent by 2029.

As total revenues contract, financial pressure on publishing houses intensifies. This pressure manifests in the disappearance and consolidation of newspapers and editorial operations, particularly acute in regional newspaper markets. The result is an increase in media concentration and reduced media plurality across Germany.

Ownership Concentration Produces Editorial Concentration

The media industry has responded to declining circulation, falling advertising revenues, and associated turnover losses through intensified competition and mounting growth pressures. The resulting consolidation imperative leads large media companies to acquire smaller publishing operations under cost pressure in order to offset overall circulation losses through expansion of market shares - following the principle that greater scale generates higher profitability. These acquisitions typically involve cost reductions through operational synergies, efficiency gains, and professionalization.

However, these strategies often conceal cost-cutting measures that extend beyond consolidation of distribution networks, printing facilities, and other secondary newspaper operations. Some of the most significant cost reductions come through workforce reduction. When large media companies acquire multiple newspapers, the merging of a large part if not all editorial operations across titles is commonplace, often maintaining only a small local newsroom with few members of staff. National news and content, ranging from federal politics, to economics and culture is then supplied from centralized editorial desks known as “Mantelredaktionen” (engl: central editorial desk). This centralisation reduces labor costs but simultaneously reduces the plurality of journalistic voices, independent editorial operations, and diverse perspectives.

The term “Mantelredaktionen” carries deliberate irony: Mantel in German denotes both the outer cover pages of a newspaper and, metaphorically, a cloak or concealment. The structure itself functions as this double meaning—editorially unified content is cloaked beneath distinctive newspaper mastheads and layouts, masking the underlying consolidation of journalistic voices and editorial independence beneath an illusion of plurality.

Over recent decades, this model has produced large regional media companies that today define the German regional newspaper landscape: Ippen Media, Funke Mediengruppe, Madsack, and Neue Pressegesellschaft (NPG). Collectively, these companies control a substantial proportion of German local news production.

From East to West: Editorial Concentration in Fewer Hands

MOM Team research on media ownership in Germany has examined extreme cases of this form of central editorial desk journalism. Patterns differ between eastern and western German media, yet structural similarities persist across both regions.

In southwestern Germany, Stuttgart's leading newspapers exemplify this model of cost-driven consolidation and editorial concentration. Stuttgarter Nachrichten and Stuttgarter Zeitung are editorially nearly identical despite appearing in distinct layouts. Since 2013, their editorial operations have been substantially merged. Following the acquisition of both titles formerly owned by Südwestdeutsche Medienholding (SWMH) through the Neue Pressegesellschaft in 2025, further consolidation and editorial integration is anticipated.

In the eastern part of Germany, Thuringia's largest newspapers represent an additional case study, and potentially one of the most extreme examples of this type of “Mantelredaktion” journalism (engl: central editorial desk journalism). Thüringer Allgemeine, Ostthüringer Zeitung, and Thüringische Landeszeitung are all part of Funke Medien Thüringen and receive their content from its central editorial desk. These editorially identical newspapers appear in the same format with only minimal layout variations. The papers have been consolidated within a single newspaper group since 1990 (formerly operating as Mediengruppe Thüringen GmbH until 2015). In this joined format it positions them among Germany's highest-circulation regional newspapers.

Both cases exemplify a trend in which media ownership concentration produces editorial concentration. Developments in eastern and western Germany differ due to distinct sociopolitical histories following the country's division. In eastern Germany, large newspaper monopolies emerged through the privatisation of formerly state-owned newspaper and media operations under the communist regime—a unique opportunity for market expansion by capital-rich western German media companies. However, this historically unique form of state-sanctioned privatisation after the collapse of the GDR (German Democratic Republic) alone did not produce these monopolies and central editorial structures. Eastern newspapers faced unprecedented competitive pressure at the time of German reunification and could only manage cost and modernization pressures through merger with western German media companies (as occurred with Thüringer Allgemeine). This development, though under different circumstances, increasingly characterizes trends in Western Germany: consolidation, digitalization, modernization and market concentration.

Inadequate Regulation and Limited Alternatives

How should Germany address progressive media concentration and homogenisation of editorial structures in journalism? The recent case of Südwestdeutsche Medienholding's restructuring and partial acquisition by Neue Pressegesellschaft demonstrates clearly that Germany's existing antitrust and media concentration law has limited capacity to effectively constrain advancing media concentration. Even the Bundeskartellamt (Federal Cartel Office) acknowledged during approval proceedings that despite evident competitive concerns, it frequently lacks legal means to intervene. The Deutscher Journalisten-Verband (German Association of Journalists) has called for antitrust law reform that more effectively prevents media monopolies and thereby preserves media plurality—an essential aspect of democracy.

Germany does maintain regulations, particularly in broadcasting, designed to prevent dominant opinion formation. However, these legal instruments no longer comprehensively address the full scope of media and opinion power—particularly in an era of digital platforms, cross-media corporate structures, and vertical integration of large media companies with extensive central and regional editorial desks. Media experts, journalists, and professional associations have emphasised for years that ownership concentration in media produces democratic deficits, both theoretically and practically, by expanding opportunities for content influence, opinion formation, and extensive control over working conditions for journalists.

Simultaneously, major publishers and media companies increasingly argue that only through further concentration and consolidation can journalism in Germany remain economically viable in the long-term. Proponents of this position emphasise that scale and financial strength are necessary to compete globally for reach, talent, and advertising revenues against international platforms in the attention economy. Only in this way can we ensure journalism can have a sustainable and financially viable future in times of major shifts and sinking revenues in the publishing and media sector.

This tension reveals a central gap in media policy: on one side stands the legitimate need for economically sustainable structures; on the other, the democratic necessity to preserve media plurality and independence. The current situation lacks a contemporary regulatory framework and a coherent, future-oriented vision for journalism that extends beyond competition and antitrust law and meets the current conditions of the media environment. However, this is more needed than ever to ensure both economic stability and viability and a diverse, independent media landscape in the digital media era. As such, to resolve this tension and find a collective response is and will continue to be a shared responsibility of the media sector, policymakers, civil society actors, and society broadly, both now and in the future.